Vulnerable children in a digital world report

On the 12th February 2018, Internet Matters published a new report, ‘Vulnerable children in a digital world’, to highlight how children’s offline vulnerabilities can help identify what types of risks they may face online so they can be provided with early intervention and specialist support to help them stay safe online.

The study, in partnership with Youthworks and the University of Kingston, used a robust dataset of vulnerable young people’s online experiences to identify how they might be more likely to encounter certain online risks. Evidence from the Cybersurvey suggested that young people with offline vulnerabilities do experience more online risk.

The study explored the risks experienced by a range of vulnerable groups including family vulnerability, communication difficulties, physical disabilities, special educational needs and mental health difficulties.

Contributory factors to vulnerability included:

- Being disadvantaged.

- Being cyberbullied or a victim of online aggression.

- Social isolation.

- Poor emotional health.

- The intersection of several vulnerabilities and adverse early childhood experiences.

- A parent- child divide: young people are digitally skilled but less emotionally mature, parents feel inadequate when faced with digital problem solving.

- Online safety education not meeting the specific needs of vulnerable young people.

- Prior trauma or neglect.

- Few, if any, models of a healthy relationship.

- Special educational needs which make it difficult to recognise manipulation.

- Communication difficulties, either physical or due to first language.

- A deep emotional need from children and young people to connect and be accepted by people they love and care about.

- Risk-taking - common in adolescence.

Summary of Key Findings

Whilst we recommend that DSLs access the full report to explore the wider context highlighted, some of the key findings relevant to DSLs in education include:

- Adversities are not present in isolation

- Vulnerable children tend to live with several difficulties

- Vulnerable children experience multiple victimisations

- Existing offline vulnerabilities significantly predict certain types of risk

- Experience of one high risk category predicts the likelihood of encountering others. Interventions require a wider and more nuanced response beyond the problem the young person initially reports.

- There is a hierarchy of risk in which some vulnerable groups are significantly more at risk than others in specific ways.

- For some vulnerable young people, going online provided a positive space to escape from or compensate for their offline reality; a way to find sensation and fun.

- The challenge is to convert knowledge into action when there are powerful emotional needs driving young people's actions, whilst being aware that young people who do not feel good about themselves, lack confidence or are unhappy or introverted, tend to go online to compensate. Banning ‘screens’ is not the answer.

- When a vulnerable young person reports a significant risk or actual harm in their online life, the steps taken should include a wider consideration of their known offline vulnerabilities and an exploration of their online experiences that goes beyond the issue that is the subject of the intervention.

Specific issues for vulnerable groups

- Isolation, weak offline social networks and poor social skills are unlikely to help develop quality friendships online

- Prior neglect can result in developmental, behavioural and emotional problems; child who have experienced this issue might seek new relationships, possibly online that provide the interaction and response they are seeking.

- Young carers miss out on advice from home; only 55% of Young Carers received advice from parents or carers on how to stay safe online compared to 62% of other young people.

- Two thirds of young people in care do report getting advice from parents or carers on staying safe online, 31% said it was ‘not good enough or useless.’

- More than half of the young carers surveyed spent five or more hours online per day. – In a workshop to discuss the survey results, young carers reported that the adult they cared for was ‘always on a screen’.

- Existing vulnerabilities predict certain online risks, but it does not show whether online experiences cause vulnerabilities such as mental health difficulties. It is likely that someone with pre-existing mental health difficulties could be impacted in different ways by their online experiences and find their mental and emotional health problems compounded by exposure to certain content or encounters.

Current Education Experiences of Vulnerable Children

- Vulnerable children lack relevant advice on staying safe online

- Online safety education often delivers a generic set of rules and warnings without addressing motivation or emotional needs, despite evidence that socially isolated or introverted teens engage in risky online behaviours

- Vulnerable children miss out on online safety education or find it does not seem relevant, given their concerns; they point out it is often given ‘too late’.

- If online safety is only occasionally addressed rather than embedded into the life of the school, it becomes more likely that vulnerable children will miss out.

- Teens’ trust in adults to solve online problems for them is low.

- Where online safety education is delivered rarely, students lose trust in adults as a source of help if or when they have online problems.

- Adults need to demonstrate engagement with online issues and maintain an ongoing dialogue with young people that is age appropriate and responsive if they are to be trusted to help.

- For some vulnerable children, one reason that they give for not being attentive during an online safety session is that they are worrying about real major problems in their life and simply do not have the capacity to view as urgent the potential risks being described in the session. They can shut it out, or feel they know it already or it ‘won’t happen to me’.

Insights for Educators

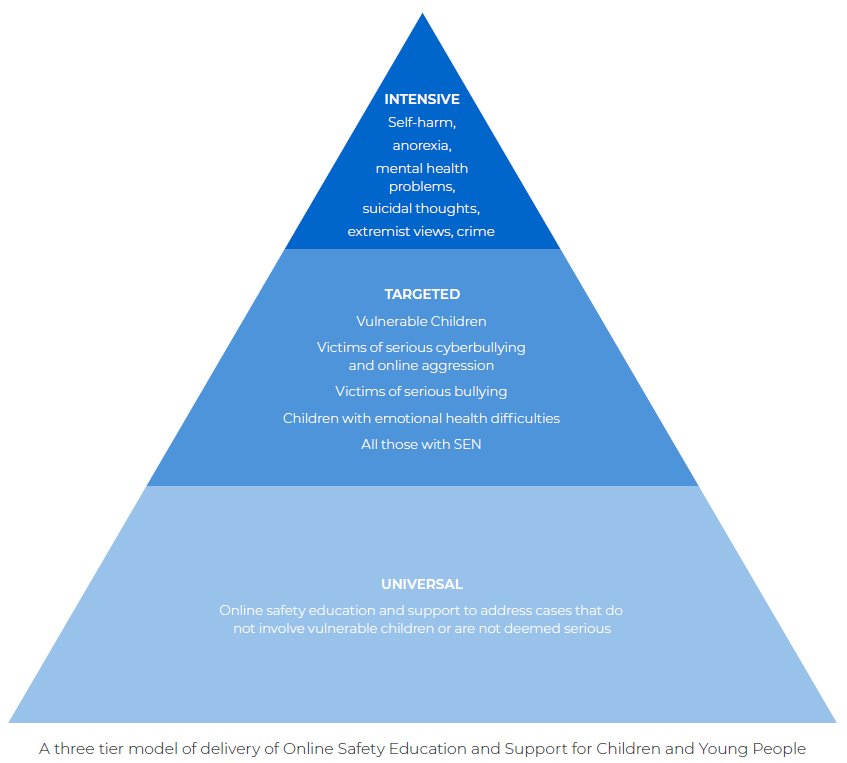

- One size doesn’t fit all

- A more nuanced and sensitive approach for vulnerable children and young people is needed, along with specialised knowledge.

- Understand how motivation outweighs rules

- New approaches to education are required because current campaigns studied primarily rely on shock tactics; scare stories followed by rules are ineffective.

- Education needs to move from a focus on personal information to concerns relevant to teenagers such as interaction, romance and sex.

- Discussions about online safety should take place in a safe, respectful and non- judgemental space.

- Consider the risk of unintended consequences of online safety education

- Educating vulnerable children in online safety is complex. For example, there is a risk that limiting or censoring discussions may overlook the way young people use social media to prevent more extreme risks. Guidelines need to be developed to accompany the delivery of online safety education so that educators are aware of how to address this issue.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of online safety programmes

- Online safety education should be delivered within a robust systematic evaluative framework. Many resources and programmes used by schools have not been evaluated by those who created or deliver them.

Conclusion

- Not all vulnerable children and young people should be automatically considered at risk online.

- DSLs should work with staff to ensure that children and young people who are vulnerable offline are given relevant, proactive and nuanced education which supports them to help them stay safe online.

- If vulnerable children and young people encounter problems online, the level of intervention and support should be well informed and responsive to any other possible risks that might be present.

Additional guidance to enable DSLs and educational settings to support children and young people with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities can be found on Kelsi.