Forget-me-not: The Importance of Retrieval Practice in English

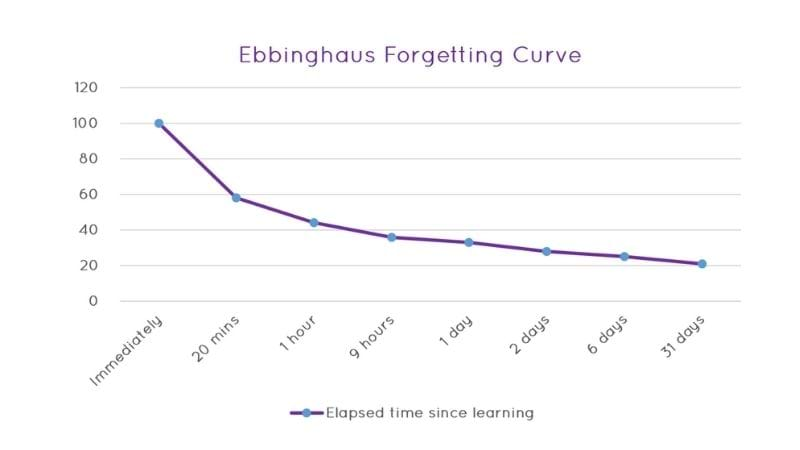

Unusually for the English specialist, I am going to start this blog off with one of my favourite graphs.

This simple little diagram really changed my thinking around the curriculum when I first saw it, and to my shame, it was probably only about five years ago that it happened. Considering it is a piece of research which first appeared in 1885, it really highlighted how much I needed to raise my game in terms of educational research.

My own failings aside, let me explain why this little graph is so important. What is outlined by Ebbinghaus in his 'forgetting curve' here, is the rate at which information is lost following the teaching sequence. It looks a bit demoralizing for teachers as we see that in a matter of 31 days, all that remains of our hard work is 21% retained by the learner. We are working our socks off to effectively teach students and yet much of that information may be eroded over what is a relatively short period of time.

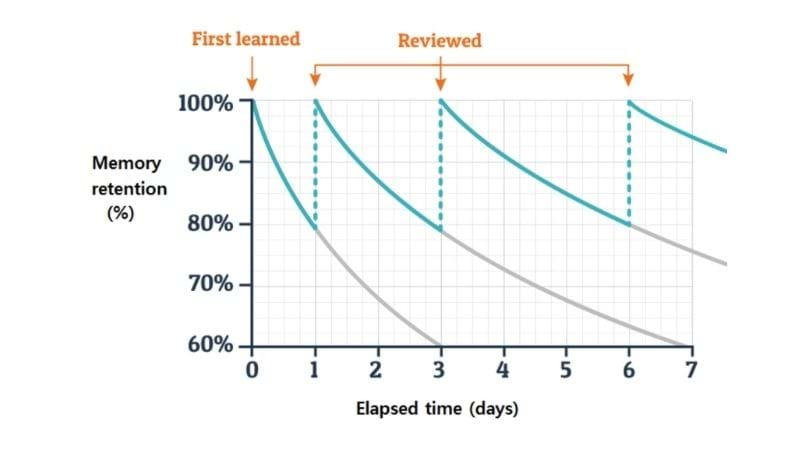

However, the information does not disappear completely, and the picture isn’t that bleak when you look at the new graph below.

Whilst the information we learn does seem to drift from our immediate memory and we begin to struggle to recall information over a period of time, we can do something about it. This can work in our favour in the classroom. If we disrupt this ‘forgetting curve’ at regular intervals, revisiting key information at different points, we can ensure that the information is retained. Furthermore, not only does this enable students to retain this information for longer, but there is also evidence that the speed of retrieval also increases. This means that some key information students can retrieve information quickly, efficiently and for a longer period of time. No longer will we have a situation where students walk into an exam, regurgitate it all onto the page and forget it forever. No, instead we will have students remembering this key information for years to come.

So, what does this mean in the English classroom?

Well, first I think it reminds us to look at the curriculum and deciding on the most important information we need students to retain over time. This should be in each unit, each term, and each year. We then need to plan how to revisit this in a meaningful way. This is different to the process of recapping, as we want to ensure students are having to think hard in order to retrieve, and ideally retrieve it with only a few prompts. Revision questions, 3, 5 or 10, as appropriate to your context, are the easiest way to drill down to this, and including some of these in the in the lessons will allow teachers and students to identify gaps and include reteaching or review as part of the process.

For example, if I were teaching Macbeth in Year 10, I would want to make sure that I regularly got students to retrieve key facts about the play, including plot, character and key quotes. However, I would also want to retrieve points from their earlier learning, for example from key stage three where they had studied another tragedy by Shakespeare or points about writing techniques other writers would use. Some of the same questions would be used on rotation, or some slight rewording of a question would be included to ensure students were really having to think about the response. For example, ‘how is Macbeth presented in Act 1, scene 2?’ and ‘what is Duncan’s view of Macbeth near the start of the play?’ It is important they think hard about it and don’t get too familiar with the responses as you develop this. As Daniel Willingham has told us on more than one occasion ‘memory is the residue of thought’ so if the students aren’t challenged as the questions are too familiar, we are not getting their memory activated. The same is true on the use of notes and materials. We want to generate deeper understanding and learning; we need to ensure students are working hard in their thought processes. This is even more important than them producing reams of essay, something else I wish I had known about much earlier in my career. It would have saved on the marking.

The other element of retrieval is that when we ask students to access something from the prior learning or their existing schemas, information becomes linked to what students already know, make the retention much stronger. Fragmented knowledge is much harder to retain (try remembering 1, 0, 6, 6, 1, 9, 18 without making a link to 1066 and the Battle of Hastings or 1918 and the end of the First World War), so linking things to what we already know or clustering information together into patters or groups will be a much more powerful way to learn. This also has implications for teaching things like grammar discretely; it will take us up to a point, but without seeing apostrophes and embedded clauses in action students are likely to forget what they are. Better still, get them to use them.

Dylan Wiliam, Professor of Education at UCL and author, has been known to say that cognitive load theory is the most important piece of research teachers can know, however, I would argue we should return to Ebbinghaus. I have shared it with staff and students alike and each time I see a little light bulb moment. There is so much to explore beyond the initial research through and there is a wealth of information about how you can use this to really ensure our students are learning. This could be a gateway to lots more exploration of what will really work for our students.

Further Reading

- Retrieval Practice by Kate Jones

- Generative Learning in Action by Zoe and Mark Enser